Authentic and loud,

Three chords and a truth that burns—

Noise becomes revolt.

(Dateline: Edinburgh) When I moved to Southern California from Canada in 1977, my musical diet changed—dramatically.

I wasn’t starving before. I was happily gorging on a steady buffet of Motown, Canadiana, Midwestern blue-collar rock, and the usual headliner suspects: Zeppelin, Springsteen and ELO. I even dipped my toe into disco once or twice—don't judge me, it was the '70s, everyone was confused.

My observation of this era was that rock'n'roll hit its rebellious teenage years by the mid-70s (like me)—experimenting with gender, style and identity. And like any adolescent, it was simultaneously raging against its elders and softening into something more mainstream.

But then I heard punk. And everything changed. Suddenly, the world was loud, fast, angry, and brilliantly unpolished.

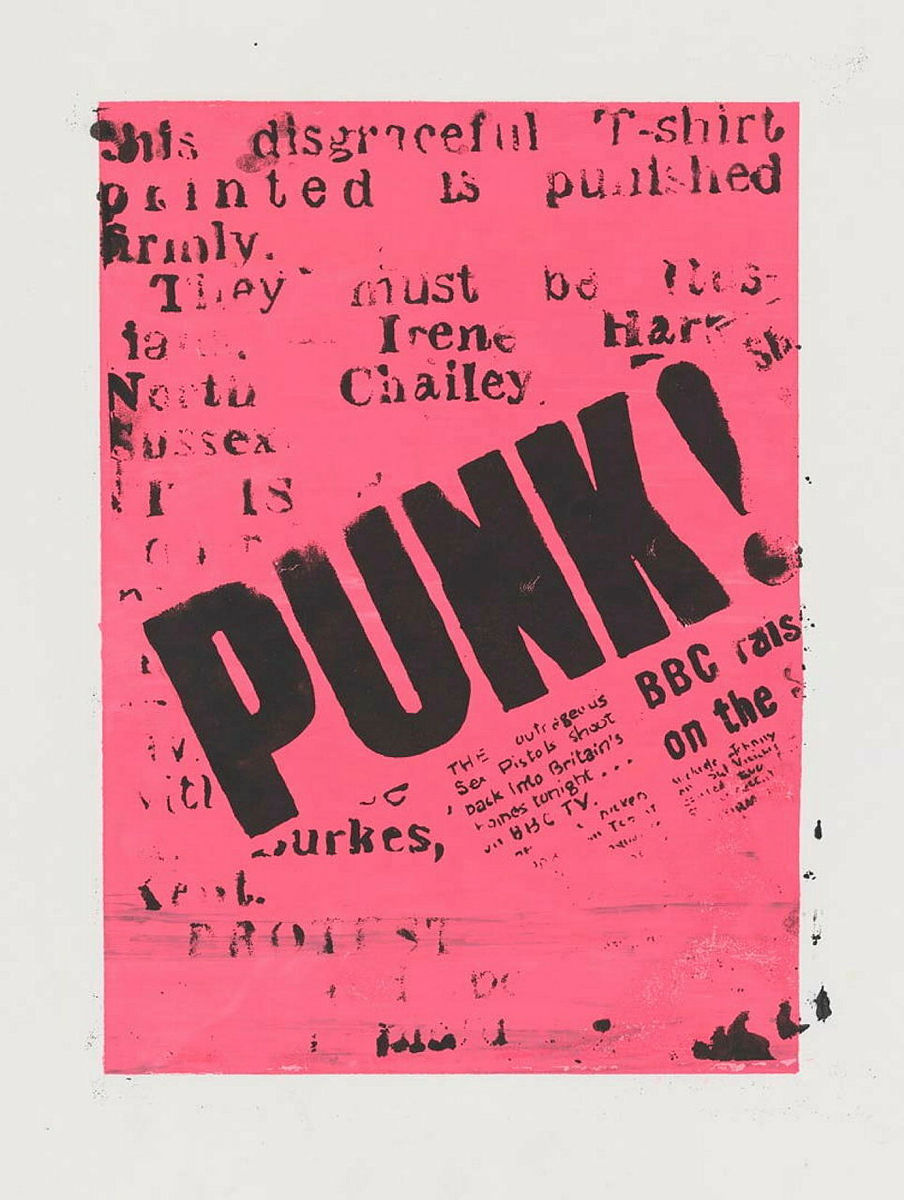

Punk wasn’t just music. It was the first full-blown subculture I followed. It was a sound, sure, but it was also a sneer, a safety pin and a solid middle finger to everything that had grown bloated, beige and boring. It wasn’t all shiny and polished. It wasn’t pretty. And it definitely didn’t give a damn about being liked.

And neither did I. I was 19.

And in that autumn, we’d head up I-5 and go to The Masque, a grimy punk club just off Hollywood Boulevard that opened earlier that summer. It was chaos incarnate. You could catch the Germs, the Dickies, the Dils, or X on a sweaty night packed tighter than a can of hairspray in a bonfire. It was always carnival-like for me. But it didn’t last long—fire marshals hate fun—but it changed everything for me.

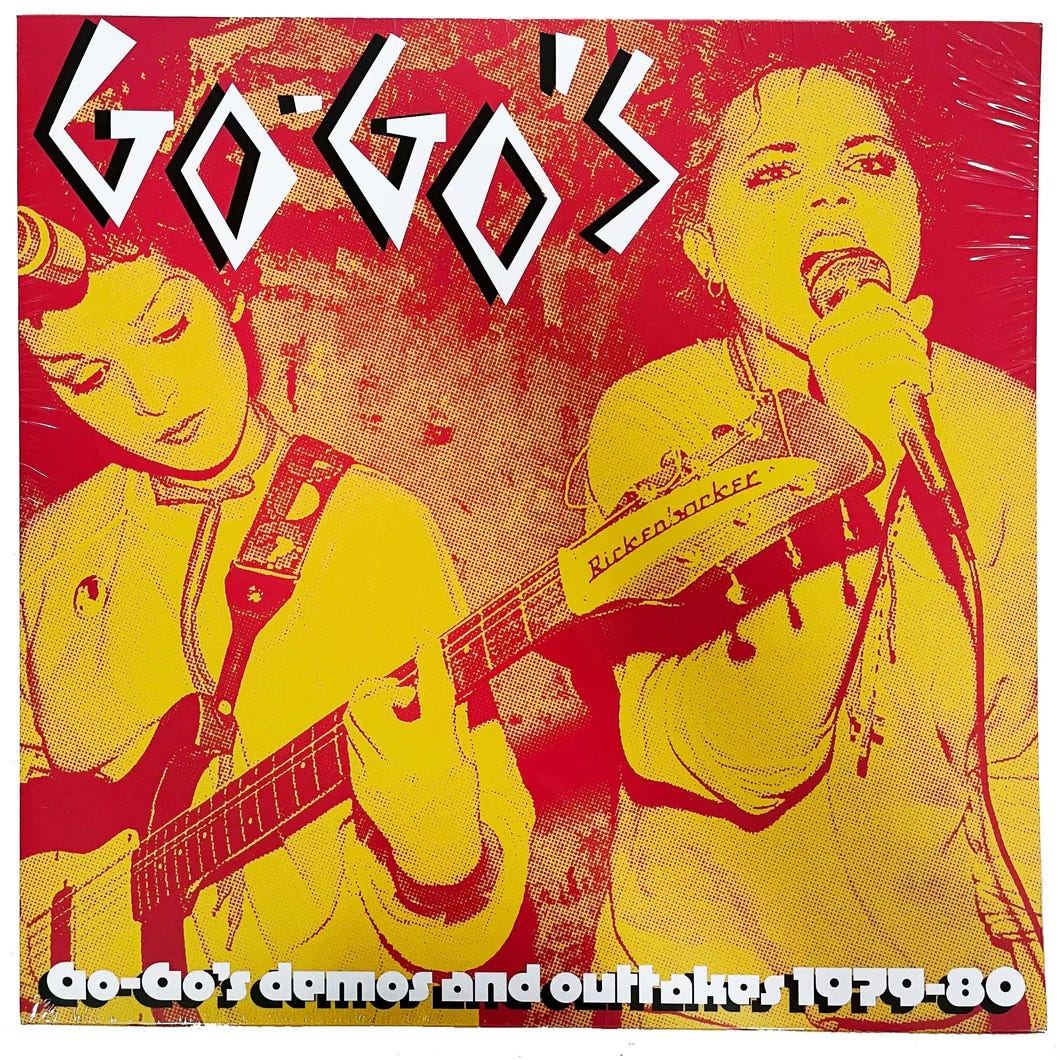

That late-70s LA punk scene was alive and pulsing: Black Flag, The Runaways, Fear, Circle Jerks and the Go-Go’s before they got all sparkly. Over in Orange County, things were, let’s just say a little...whiter. Suburban boys from broken homes moshing in surf-punk rage. Social Distortion, Agent Orange, Adolescents—good music, maybe, but a little too blame-the-others Klan-curious for my taste. Punk was supposed to be against The Man, not practicing being him in jackboots, like early ICE-trainees.

Those Orange County punks were like angry mall Santas—red-faced, jaded and slightly terrifying to children. I wasn’t looking to get spit on or stomped in a pit by skinheads trying out for a new kind of fascism. Not my tribe. Besides, swastikas are a dead give-away, right? The decline of western civilization indeed.

No, I was drawn to punk that punched up. Punk that barked truth to power. Punk with brains.

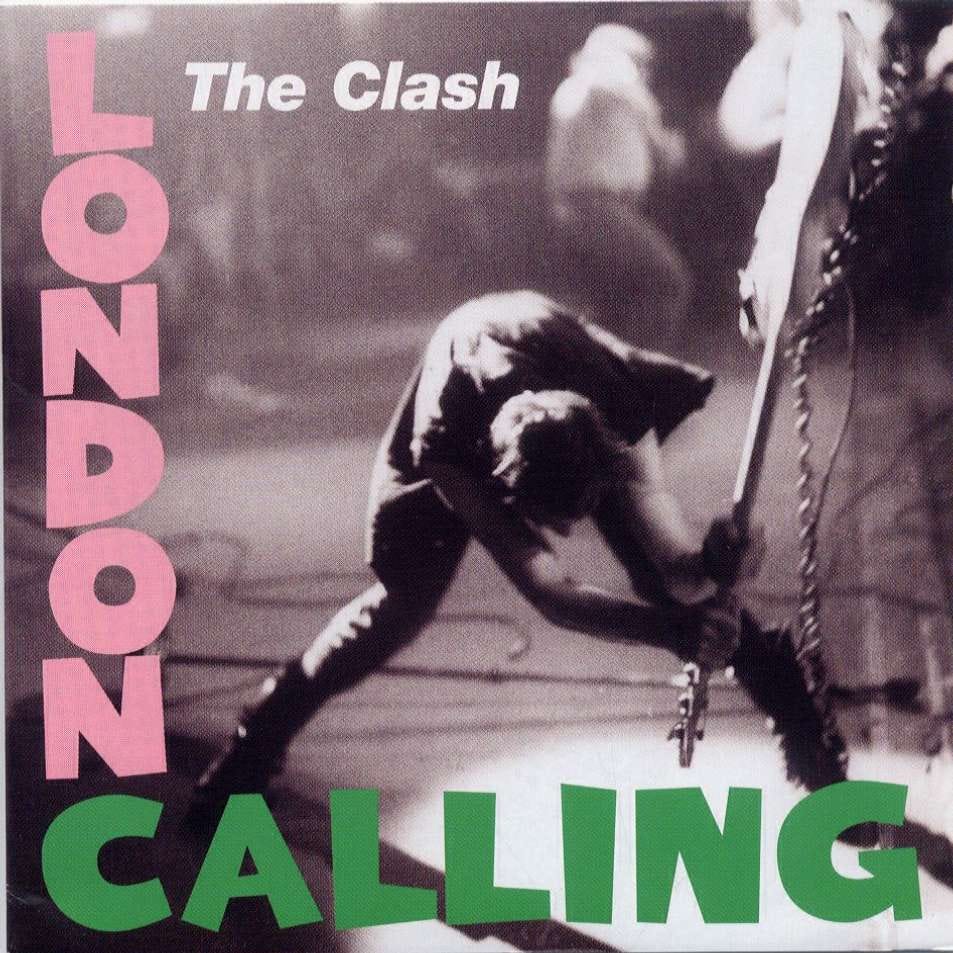

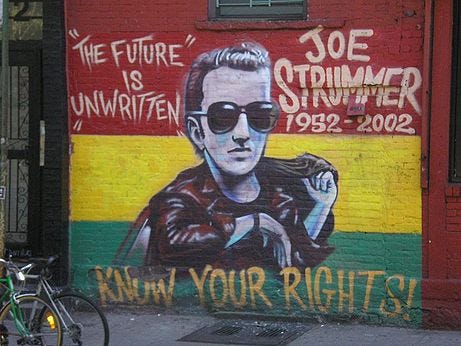

Admittedly, there wasn’t a lot of virtuosity in that early manic punk—unless you count being able to scream about injustice for 90 seconds without your vocal cords exploding—but The Clash could play. They were different. They didn’t just rage, they radiated purpose. They were loud and literate. And they changed my life.

Let me say that again for the kids in the back: The Clash radicalized me.

Sure, the Sex Pistols got all the headlines, but they were the drunken grenade at the wedding. The Clash were the resistance pamphlet slipped under your door. Joe Strummer’s voice was my political education. I’d grown up in a union town (UAW Local 200), raised on my Irish grandmother’s rants about Walter Reuther and FDR. I already had a healthy suspicion of the billionaire boys club bullshit—I knew all about Grosse Pointe (the park, the city, the farms, the woods and the shores too). But The Clash brought it all into focus. They weaponized guitars. They taught me how to question power, reject greed and fight the creeping normalcy of injustice.

Cheeky bastards, they also introduced me to reggae, dub, ska, rockabilly (and proto-hip-hop) on the side—because even revolutions need rhythm.

That said, I wasn’t a punk punk. Never shaved my head. Never pierced anything visible—except for that small diamond I’ve been wearing in my left ear since the 70s. I flirted with fashion—leather ties, chromatic shirts, plaid platform shoes—but I mostly stuck to Levi’s and a t-shirt. Still do. I was there for the message, not the WWE mosh pit. Let’s just say I was a thinking man’s punk. And definitely not into the whole spitting-on-stage-as-a-form-of-communication thing. Punk wasn’t a costume for me. It was a mindset.

But let’s rewind a little. Please grab a chair. No, this won’t be on the test, but it matters.

Armchair pontificators will give you all kinds of high-minded reasons for the birth of punk. Some say it arose from a youth crisis—Beatniks, Teddy Boys, rockers, Mods, Hippies...all tried and failed to stick the landing. Peace and love had its shot. We got threats of a nuclear winter, Reagan and Thatcher instead. Others point to the context: unemployment lines, lies from on high, post-Watergate hangovers, wars we didn’t win, and Cold War nihilism creeping into our cereal. Some say it was just the inevitable backlash to corporate arena rock’s bloated excess—bands that spent more time on laser shows than lyrics.

And yeah, punk was a rejection of all that. But it was also something simpler: authenticity. Punk didn’t care what you looked like or how well you could shred or sing like Roy Orbison. It was about getting up, plugging in and letting it rip. Punk didn’t care if you could play—it cared if you meant it. Virtuosity was for Yes albums. Punk was for now. Rock and roll was supposed to be rebellious. And by golly, Billy Joel, The Eagles and The Cars didn’t sound very rebellious to me in the late 70s. Because if rebellion had a sound, it wasn’t a 12-minute Jethro Tull flute solo—it was two minutes of someone yelling about rent.

Pick your reason. They all work. Or none of them do. And that’s okay, because that’s punk too.

Oddly, unbeknownst to me, proto-punk was already in my bloodstream before I had the vocabulary. I grew up just across the river from Detroit, where MC5, ? & the Mysterians and Iggy Pop were doing in-your-face unholy things to amplifiers before anyone in England had even unsafety-pinned their nappy. “Kick Out the Jams Mother Fuckers”? That’s a punk manifesto in eight syllables. Iggy was punk before the label existed. Shirtless chaos, raw energy…and Detroit as hell.

Meanwhile in New York, CBGBs was brewing something special too—The Ramones, Patti Smith and Blondie. It was loud, literary and ready to pounce. Across the pond, the Sex Pistols were puking on TV and giving middle England a collective panic attack. (Some argue that The Kinks 1964 LP "Kinks" practically invented punk (and metal too) with their blast “You Really Got Me.” Let’s call it proto-punk. And there was a lot of it in the 60s if you looked hard enough for it.)

Anyway, by the time I arrived in Southern California in ’77, punk had arrived.

Not everyone got it. The Malcolm Mclaren created Sex Pistols tried to bamboozle the world releasing their one, and only, studio LP Never Mind the Bollocks in 1977, featuring “Anarchy in the U.K.” and “God Save The Queen”. It charted at #1 in the U.K. But it spoke to angry Brits not angry North American’s like me, and only hit #106 in the U.S. American’s simply weren’t buying punk or the Pistols. But to a certain kind of kid, it was exactly the gut punch we needed.

Punk here didn’t sell out stadiums. It sold ideas.

And if you listened closely, the good stuff—the real stuff—wasn't nihilistic. It was furious because it cared. The world was broken, and punk refused to pretend otherwise. It was the musical equivalent of Ralph Nader screaming into a feedback mic. And as it turns out, I once had a long car ride conversation with Nader, which only deepened my love of disruption and distrust of corporate overlords. He told me The Man’s real kid. And he was monetizing everything, sucker.

Even back then, I didn’t want to be a sucker.

So punk taught me that music could be a weapon. Punk taught me that noise can be a political act. (So did my neighbor’s leaf blower, I might add, but only one changed my life.) That being pissed off was a legitimate artistic position. That conformity was a prison. That three chords and a truth beat the hell out of a 20-minute drum solo about nothing—while your bandmates went backstage and sniffed an eight-ball. And…that it was better to offend than to bore. (That could be my longtime dinner party motto?)

I liked bands that got it—X-Ray Spex with their feminist fire, X with their snarling poetry, The Jam and Buzzcocks with their infectious energy. I didn’t need S&M bondage pants or groupie cred. And I didn’t need a mohawk to rage against the machine—I had sarcasm and student debt. What I needed back then was a reason to believe.

And I did.

Then came the fade out. Hardcore took over when someone spiked the Kool-Aid with testosterone and forgot the melody—full of rage but less nuance. White suburban took over punk with their homophobia and overt racism. Suddenly punk was more punch than politics. The smart kids drifted into New Wave, post-punk, or went quiet altogether. But for me, the spark remained.

The truth is, punk never really died. It just mutated. It leaked into hip-hop, into indie and into actual activism. Rage Against the Machine? Descendants of The Clash. Billy Bragg? Carrying the torch. Public Enemy? Same message, different beat.

Me? I stayed a Levi’s 501-wearing, bullshit-sniffing, Clash-loving, proudly unpolished punk sympathizer. I’m not storming stages or dodging spit anymore, but the fire hasn’t gone out. Even at 67, the wife—bless-her-heart—says I still got it. I just don’t remember what it is?

And if you ever find yourself in Vegas—yes, Vegas—drop by the Punk Rock Museum. Nothing says “stick it to the man” like curated anarchy next to a slot machine. They even have a gift shop, I hear.

Thanks for the privilege of your time, it is the most precious thing we have, and I appreciate it. Be well.

William D. Chalmers © 2025 All Rights Reserved.

Great sentiment! I didn’t grow up in a big city so I didn’t have the angst. I did however get approached by a few nuns one time and they said I needed to dispel my demons. I told them I was through my art. Keep on trucking’ Bill!